by Nick Taylor and Barbara Nevins Taylor

updated June, 2023

A trip to Sardinia took us through Rome. An overnight on the way reminded us of the pleasures of the Eternal City, and we decided to take a little extra time on the way home to reacquaint ourselves some more. We wanted to eat and drink like Romans, wander the old markets and piazzas, admire the architecture and the art, and even dodge the throngs of Vespas that buzz residents from home to work and back again and add to the city’s energy.

We remembered our stay, years before, at a small, old hotel in Parione, one of 22 administrative districts or rioni into which Rome is divided. It’s the neighborhood, about halfway between the Colosseum and Vatican City to the west across the Tiber, where strollers enjoy the fountains of the Piazza Navona and browse the shop stalls of the Campo de Fiori.

The Hotel Teatro di Pompeo arranged for a driver to meet us at the airport. This small luxury was especially welcome after our overnight flight from New York on the way to Sardinia. It cost more than a train or a bus, but we could relax without schlepping luggage, and enjoy a hassle-free ride into the city.

Our ride passed from a freeway onto wide, shaded streets lined with apartment buildings and gradually entered the labyrinth of an older Rome of weathered buildings on narrow streets originally meant for chariots and carts. After tight turns and one scraped fender, the driver dropped us on the cobblestones outside our hotel, where the Theater of Pompey stood 2,000 years before. Archeologists think this is near the Curia of Pompey, the meeting hall where Julius Caesar was murdered on March 15, 44 B.C.

The three-star hotel was exactly as we remembered, simple, extremely clean with an excellent concierge. We met several Italian business people, from far-flung towns, taking advantage of the modest prices and the great location.

On that first night, we took the advice of the concierge Amerigo. We asked where he would eat and he said, “Ah, I would walk past two restaurants I like and look at the menus. They are very small. Maybe they have twenty items on the menu. Then I would choose the one where they had what I wanted to eat.”

We let him book us into Ditirambo on Piazza della Cancelleria. We could only get a late reservation and that was fine because it gave us time to walk. We headed out of our neighborhood, through the Campo di Fiore onto Via dei Banchi Vecchi, where we spied an attractive mix of people talking and laughing over glasses of wine.

The place is called Il Goccetto even though the sign says Vino (wine) Olio (oil). No matter. Inside the wine bar, in what was a 17th century palazzo, we found locals at the small bar and tables, plenty of atmosphere, good wine, and small bites.

We could order by the glass, or pick out a bottle from the shelves.

We took the bartender’s recommendation for two glasses of local white and sat back and watched the show.

A little while later, we sauntered back to toward the Campo di Fiore and found Ditirambo.

The small two-room restaurant was filled with a mix of locals and tourists. We ordered a bottle of Etna Bianco and fell into the menu. Barbara ordered baccala to start, and Nick chose a smoked duck breast sliced as thin as prosciutto.

For our mains, Barbara chose the Roman favorite Cacio e Pepe, a simple dish of pasta, parmesean, oil and pepper.

Nick ordered pasta with zucchini flower, pork cheek and goat cheese.

We toasted to Amerigo for making the excellent suggestion and congratulated ourselves for deciding to overnight in Rome. The next day we headed to Sardinia, already looking forward to our return to Rome for two nights on our way home.

Ten days later, we returned and learned that most Roman restaurants close on Sunday nights. We did have plans for later though.

Caesar was our theme for the night.

Our friends Ray Parisi and Ben Moore raved about a tour and light show they’d seen that highlights the urban renewal project Julius Caesar used to build the monument to himself that became Caesar’s Forum. The emperor’s grand plan razed private buildings and displaced local residents. Two years after it started he was killed and he was long gone when it was finished by Augustus in 29 B.C.

At the suggestion of Ray and Ben we booked for a 10 p.m. show a month or so earlier. That gave us enough time to walk from our hotel, find a restaurant near the forum, and then enjoy the show.

Bright flowers sprung from pots beside front doors and terraces and balconies were awash with greenery on our work through the old neighborhoods.

And the streets themselves were as vibrant, buzzing with scooters and the bustle of outdoor restaurants where waiters gathered up espresso cups and served aperitifs to early diners.

We passed through the Via del Portico d’Ottavia, the main street of Rome’s small Jewish ghetto. This is the home of the Roman-style artichoke, cariofi all Giudia. Its umbrella-shaded restaurant tables were starting to fill up, and we thought we would try to find a restaurant closer to our destination.

We walked past the front of Rome’s Great Synagogue,

looked across the Ponte Fabricio to Tiber Island in the middle of the river, then turned away from the river into a confusing maze. We finally climbed a set of stairs from one street level to another and found the address we wanted, where a sign on the door announced the restaurant closed. So much for not calling to reserve.

We retraced our steps back to the Via del Portico d’Ottavia. Now we were in a hurry, and when we spied an open table inside Nonna Betta at No. 16, we grabbed it. The restaurant was long and narrow, hung with frescoes of 19th century ghetto scenes, lighted by rows of chandeliers.

As we looked over the kosher Italian menu, the very blond kids at the next table were shoveling down spaghetti and popping up to take pictures of each other. Their long-suffering and very patient chaperone told us that they were from Norway and soon they filed out for the next step in their adventure.

We ate in a hurry and then hit the streets again headed for the Forum of Caesar.

We walked past the monument to Victor Emanuel and along the Via dei Fori Imperiali toward Trajan’s column to the spot where we descended to the ruins of the ancient forum.

We joined the group for the 10 p.m. Caesar show. You can see the Forum of Caesar or the Forum of Augustus, or both. The shows run for 40 minutes each from April through November and is 15 Euros or 25 Euros for the two.

Rome has always built over its past, and then dug it up again. Julius Caesar pioneered the concept of eminent domain, the taking of private property for public use, when he persuaded the Roman senate to buy the buildings he took down to build the forum as a monument to him. Rome kept building and the forum was eventually submerged. Still later, excavations made to build the street that spans the imperial forums revealed again Caesar’s forum and those of Augustus, Trajan and Nerva.

The steps down from the Via dei Fori Imperiali deposited us among the remains of the plaza once surrounded by government buildings. We stood in a world of denuded columns, crumbling arches, stone pathways and steps to buildings reduced to tumbled stones and scattered marble. The air seemed charged with lost magnificence.

We put on earphones and the voice of Piero Angela carried us into that magnificence. Angela’s music-augmented narration was great, but the tour’s brilliance lay in vivid projections on the areas unearthed by excavation of what had once existed there. As we walked, what had been appeared on what remained: buildings rose, arches framed bas reliefs, the handlers of money weighed coins, the statue of triumphant Caesar remounted its stone horse, Rome spanned the known world.

When we emerged at the tour’s end on the level of the street above, we felt exhausted to be back in the present. Or maybe it was a day that started in Sardinia and ended more than 2,000 years earlier in ancient Rome. And modern life got more attractive quickly when we spied a taxi and hailed it for the ride back to our hotel.

The next morning, we had breakfast at Hotel Teatro di Pompeo in a room that huddled under a vaulted ceiling that was part of the original Theatre of Pompey. We discovered that the Galleria Borghese, which features Caravaggio, was closed on Mondays. So we mapped out a plan to visit the Caravaggios in the nearby churches.

But first, we had the market in the Campo di Fiori to explore. A short passageway adjacent to the hotel led us into the campo filled with stalls.

We browsed our way past vinegars and wines, fruits and vegetables, clothes and hats.

A sign on a balsamic vinegar stand warned us sternly against what we might find at its competitors.

Nick stopped, found a crushable Italian-made straw hat for 20 euros.

And we moved on to the magnificent Piazza Navona with its glorious fountains and ancient obelisk.

Obelisk, Piazza Navona, Rome, Photo by ConsumerMojo.com[/caption]

Obelisk, Piazza Navona, Rome, Photo by ConsumerMojo.com[/caption]

Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed the centerpiece, the Fountain of Four Rivers in 1651. The riotous homage to Christianity features a lion, a horse and muscular river gods of the Nile, the Danube, the Ganges and the Rio de la Plata, representing Africa, Europe, Asia and the Americas.

Bernini had not been the first choice to design the fountains, but he did fix up the Moor Fountain originally designed by Giacomo della Porta. We watched a group of high school students lounge near the water splashing from funnels blown by man-beast statues and a stone Moor wrestling with a dolphin.

Della Porta also designed the Fountain of Neptune at the far end of the Piazzo. But while he created it in 1574, it remained unfinished until 1878.

This was a perfect warm-up for our Caravaggios. Nearby we found the Church of St. Louis of the French, or Saint Louis des Français.

Its Contarelli Chapel has three fine Caravaggio paintings depicting stages in the life of St. Matthew — his calling, his inspiration, and his martyrdom. It wasn’t the Galleria Borghese but we got a closeup view of three magnificent paintings.

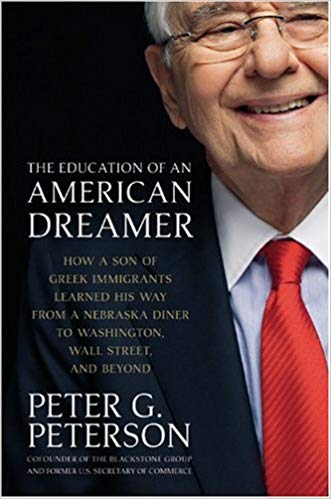

A little Roman shopping seemed in order and Nick laughed as he recounted a story the late Blackstone Group co-founder Pete Peterson, whose autobiography he helped write, told him.

Peterson said he and his friend David Rockefeller had gone into Gucci’s flagship store on the Via Condotti to look around. Pete saw a briefcase he liked and bought it. David bought nothing, but as soon as they were outside on the street he asked a passerby if there were a reasonably-priced leather goods store anywhere nearby. “I know what you mean,” the man said, “Only a Rockefeller can afford to shop at Gucci.”

We browsed Rome’s high-end designer stores and Nick, like David Rockefeller, went down the price pipeline to Massimo Dutti — owned by a company, headquartered in Spain, despite its Italian name — and found a few shirts to invest in.

Nick also made a great discovery. He found prescription medication he uses, sold over-the-counter, for far less than he would pay in the states, in a retail store.

We caught a late lunch back in our neighborhood at Hosteria Grappolo d’Oro on the Piazza della Cancelleria.

Nick then tucked into the hotel for a siesta while Barbara walked on in the old part of Rome looking for a hairdresser and a handbag without logos.

A short walk into the Centro Storico, Barbara found Frandi on the via Giubbonari, a small shop filled with handbags of all styles and colors. While she found the bag she wanted, the best find was Leo Limentani.

He explained that he was a retired engineer and helped his wife, who owned the store. When Barbara spotted a Hebrew calendar on the wall, the conversation turned to history.

Leo grew up in the building that houses the store, and so did his father. He said his father, his uncle, and other Jewish boys who lived in the building, were among the 4,733 Jews deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943 when the Germans invaded northern and central Italy. Only 314 survived, Leo’s father among them, and he returned to via Giubbonari, “It was a miracle,” Leo said. How did he survive? “It was a miracle,” Leo repeated. “I wouldn’t be here today.”

He pointed out two brass plates sunk in the cobblestones in front of the building to honor the young men killed by the Nazis.

But then, this being now, there was the selfie.

Both buoyed and sobered by the conversation, Barbara went on to look for a hairdresser and found Stefano Potrich right near the hotel.

The blow-dry was just right.

On our trips through the passageway to Campo di Fiore we passed a small jewelry shop, on the side of the hotel, that featured handcrafted metal work.

His sign says Restauro Antichata, or historic restoration, but what we saw had clean, modern lines.

Barbara couldn’t resist and bought a bracelet from the owner/jeweler.

For our last meal in Rome, we had made a reservation in advance at Pierluigi, on Via di Monseratto. Just as darkness fell, we walked diagonally across the Campo di Fiori, hit the Piazza Farnese a few blocks farther on, and when we turned onto Via di Monseratto we could see the Piazza de’ Ricci and Pierluigi’s umbrellaed outdoor tables in the near distance.

As we approached we saw black cars at the curbs with drivers in slim-cut, dark suits killing time nearby.

The greeter showed us to a table at the corner of the building and the quiet street. We ordered due prosecci and studied the menu.

It was expensive but not outrageous. Since Pierluigi calls itself the first fish restaurant in Rome, we started with sea scallop carpaccio and a stuffed zucchini flower, ordered a bottle of Etna Bianco to go with the rest of the meal, split an order of pasta with clams and bottarga, and finished up with fried fish and baked sea bass.

It was all good — the food well-prepared and nicely presented and the staff was attentive.

The local men at the next table argued about art and politics with enough English thrown in that we followed snatches of it, and we had lovely people to watch on an equally lovely and warm evening.

The scam, when it came, was a relatively small one. Our waiter, a graying man probably in his mid-50s, spoke good English and had a way of flattering our choice of orders. So after I gave him a card and he brought the slip back to be signed, it really wasn’t a surprise when he leaned over and said quietly, “You know, service is not included.” Which was a lie. Service is included at Italian restaurants. You tip, if you choose, for exceptional service, usually by just rounding up to the nearest multiple of 5 or 10.

We had a fine evening. So Nick signed the slip for 231.93 euros ($199), left a 20 euro note on top of it, and we retraced our steps through the soft night to our hotel atop the remains of the Theater of Pompey.

A driver arrived at 7:45 the next morning, Tuesday July 3, to deliver us to Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci Airport for our flight, via Madrid, to JFK and home.

Arrivederci Roma. Until next time.

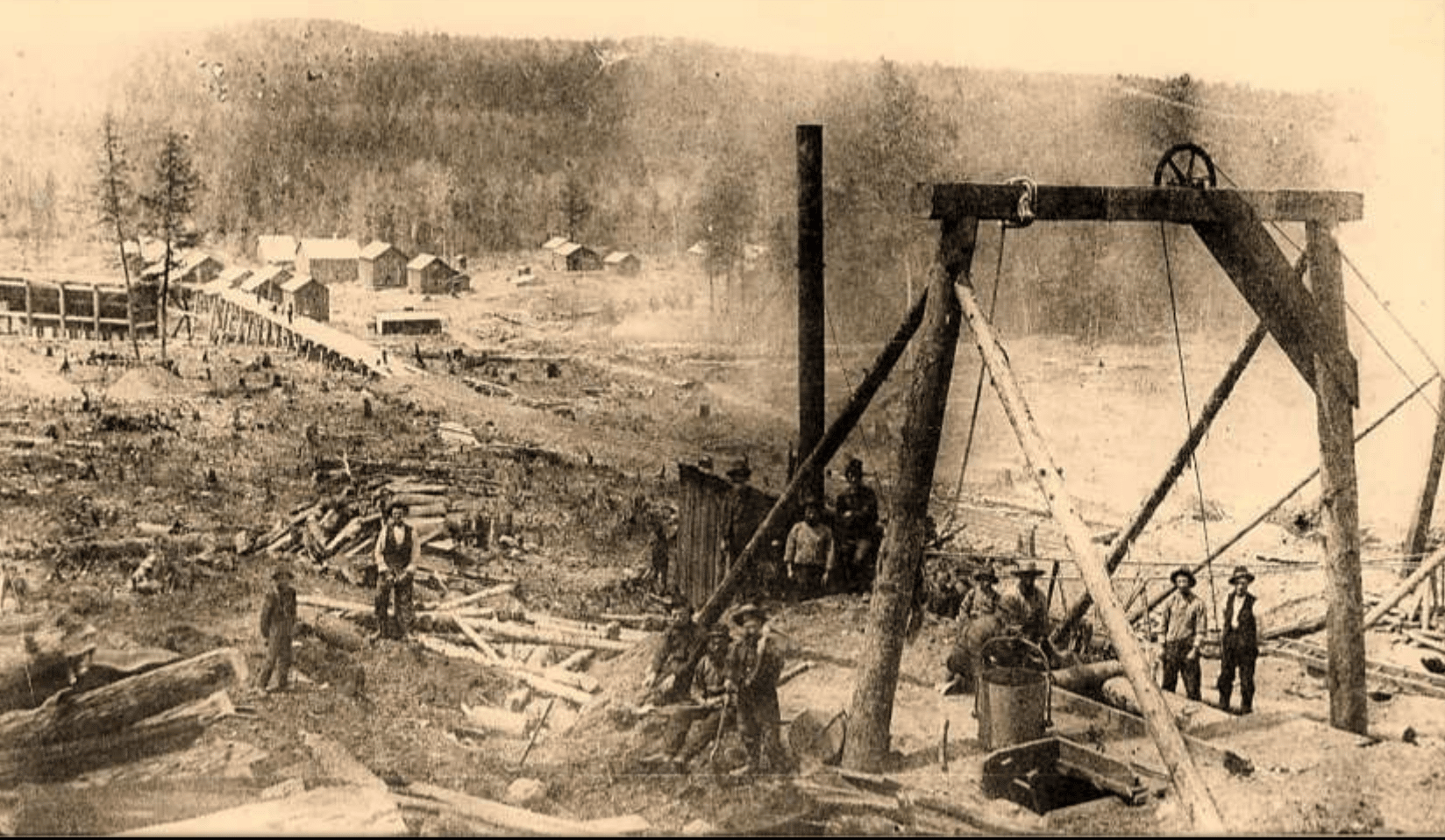

Mamie Parent Unger at my parents’ wedding in 1942. She was still good-looking.

Mamie Parent Unger at my parents’ wedding in 1942. She was still good-looking.

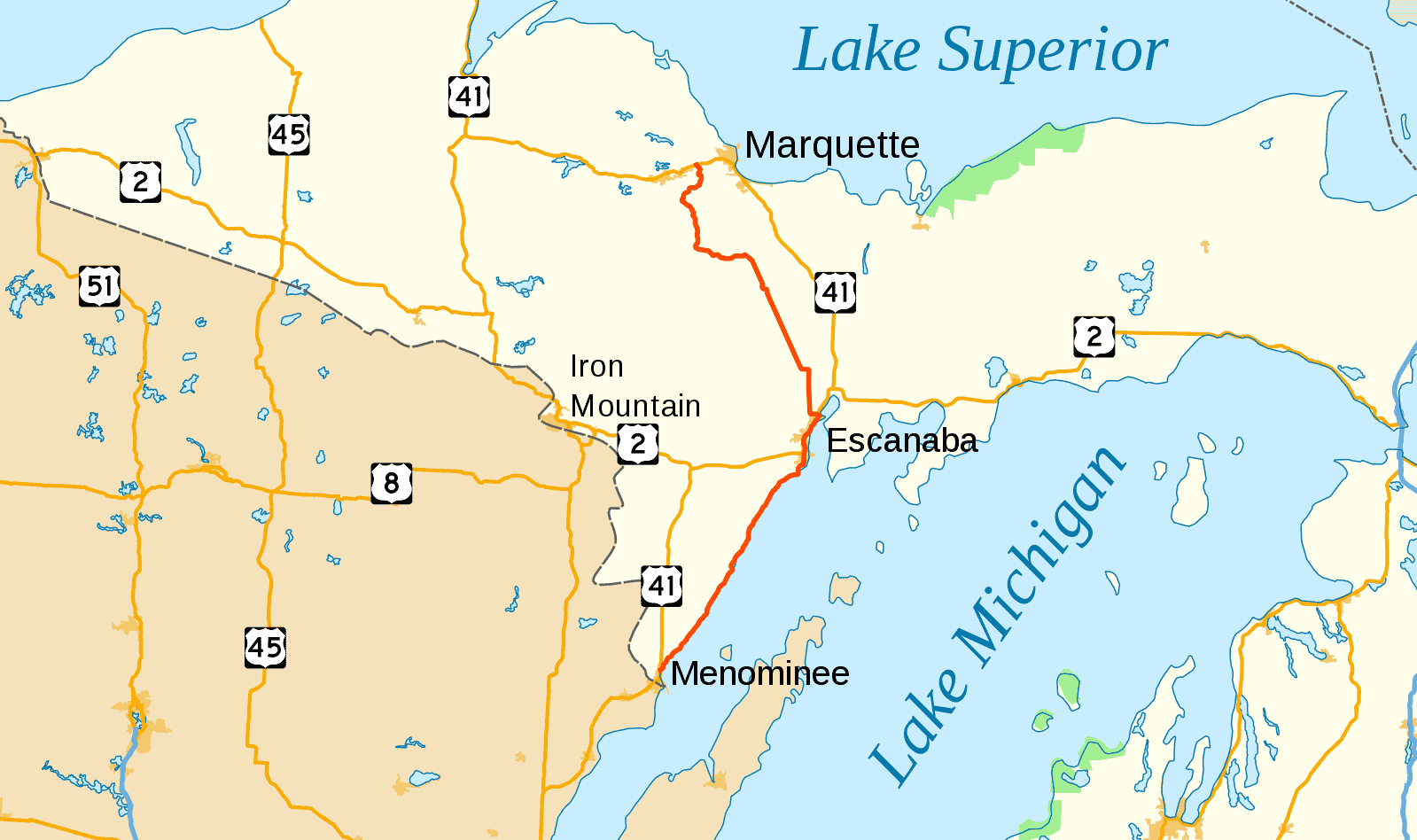

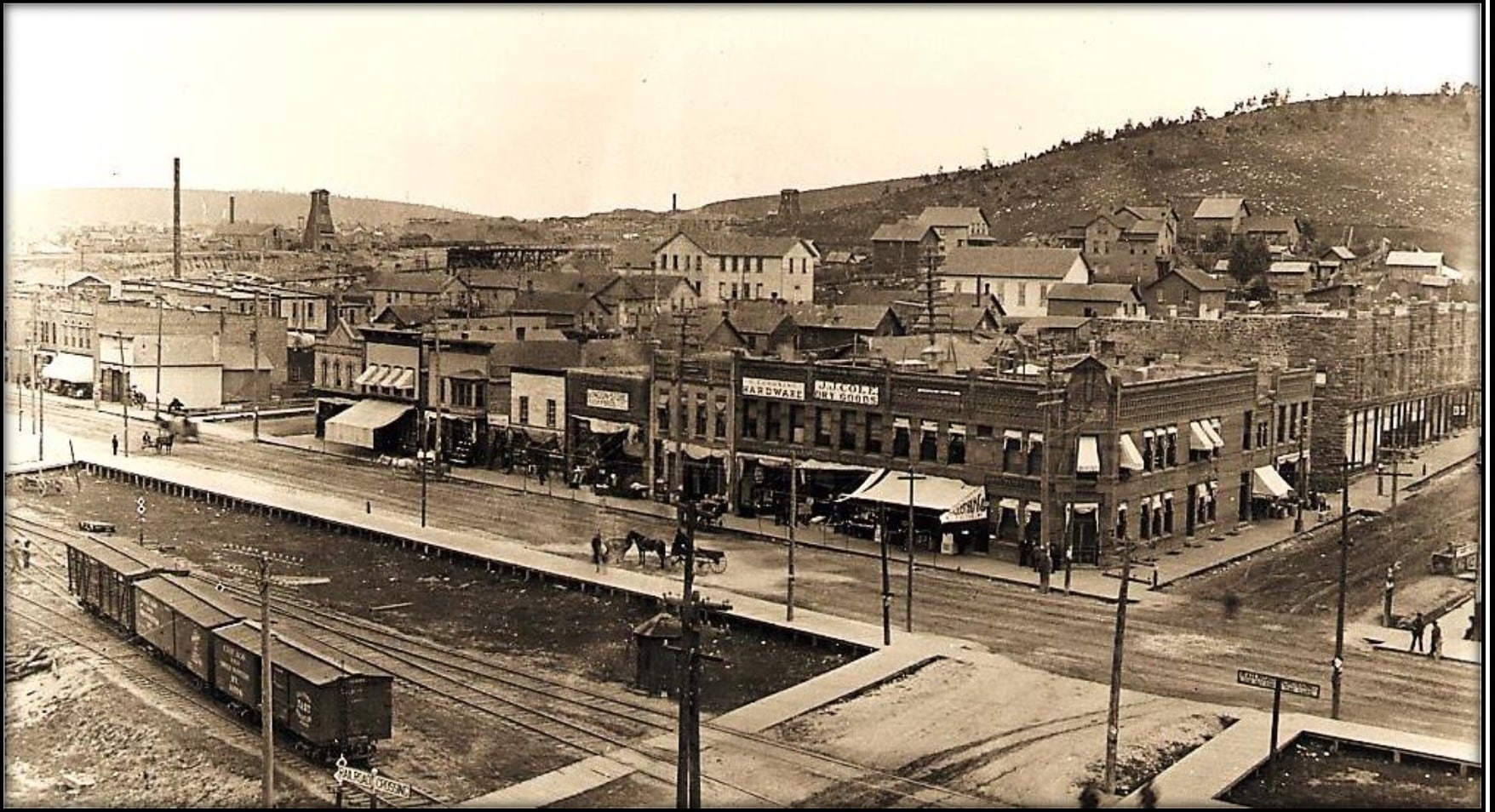

Iron Mountain Cemetery Park. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

Iron Mountain Cemetery Park. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com My grandfather’s grave in Iron Mountain’s cemetery.

My grandfather’s grave in Iron Mountain’s cemetery.