by Nick Taylor

We were in the third day of our journey now, heading to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and the town of Iron Mountain. I wanted to explore a part of my past I’d neglected all my life. I’d visited English churches, villages and schools where my father and his forebears had set foot, but never been to where my mother came from. Call it a roots tour if you like. I had no idea what we’d find.

I understood a little about what this journey might yield. Barbara and I had traveled to Eastern Europe where all her grandparents came from. They fled brutality and anti-Semitism long before the Holocaust. And there was little left of the life they remembered.

For Barbara it had been important to go, to breathe the air, to try to understand what made her people who they were. It was the same for me.

My mother’s family’s story is a little different. She and her siblings left Iron Mountain long ago too, but their parents and grandparents and other relatives are buried there.

There’s little left there of the lives they lived, but what we found surprised me. My family was a big part of the Iron Mountain’s history in the days of its iron mining boom, and their departure mirrored its decline. Their story also showed me something about how a family loses its Jewish identity and culture.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

After our fill-up at West Branch, we reached the straights of Mackinac, pronounced Mack-in-awe, in less than two hours. The straits connect Lake Michigan and Lake Huron and the bridge across them, the Mackinac Bridge, connects lower and upper Michigan. At five miles long, it’s the 27th longest suspension bridge in the world and its span between anchorages is the longest in the Western Hemisphere.

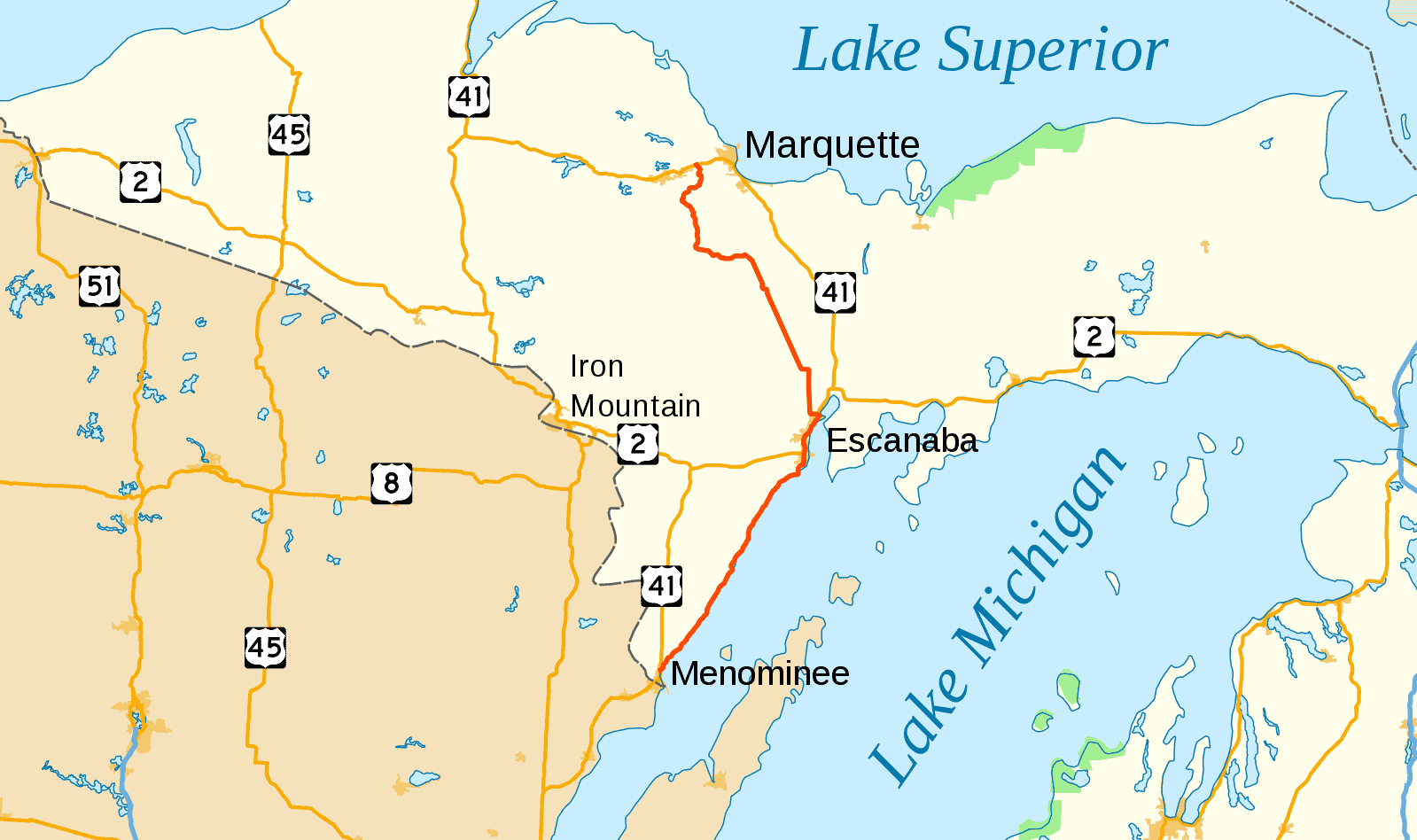

We crossed the bridge and turned west on US 2 toward Iron Mountain.

The drive along the lightly-traveled two-lane was beautiful despite a spotty rain. We passed pristine sand dunes as we followed the shore of Lake Michigan. After some time the lakeshore fell away and we moved inland. To our right, in the miles of territory between us and Lake Superior, lay state and national forests, farms, and small towns. The UP is full of natural scenic destinations.

Hunters and fisher people love this area because it’s sparsely populated and unspoiled.

Finns, Norwegians and Swedes were original settlers here. We got a reminder of that when we drove through the town of Norway as we neared Iron Mountain. We also saw signs along the road for Cornish pasties, a culinary import of the miners who arrived from Cornwall in the 1880’s to work in the iron and copper mines. Mom used to talk about how she loved pasties. She said, “The miners carried them in their lunch pails and heated them on their shovels down in the mines. We had them on washday with a big fat dill pickle or chow chow. That was a meal I often dream about.”

Iron Mountain was quiet when we drove into town that Saturday evening. We saw empty streets lined by old, low buildings, and few cars or pedestrians. It was a small town in the middle of its weekend lull. I frankly was a little disappointed.

We drove from the sleepy downtown to the outskirts and the Pine Mountain Ski and Golf Resort, where we had a reservation.

On weekends, at least, it seemed the action in Iron Mountain was out there. Fred Pabst of the beer family had cleared Pine Mountain before World War II and installed one of his rope tows to lure skiers to the area. After the war, a pair of 10th Mountain Division veterans bought and improved it. Now it’s home to one of the world’s highest manmade ski jumps and regular international competitions. In summer golf takes over, and the course is rated one of Michigan’s best.

Sitting in the restaurant, filled with jerseys and photographs of Upper Peninsula sports greats, I did a computer search for Iron Mountain history and found websites rich with old photos and details. Historian William J. Cummings was credited in every case. I tracked down his phone number and called him. He answered and was surprisingly gracious about an over-the-transom Saturday night call. He provided a wealth of information, then and later, that put into context my mom’s accounts of growing up with her family.

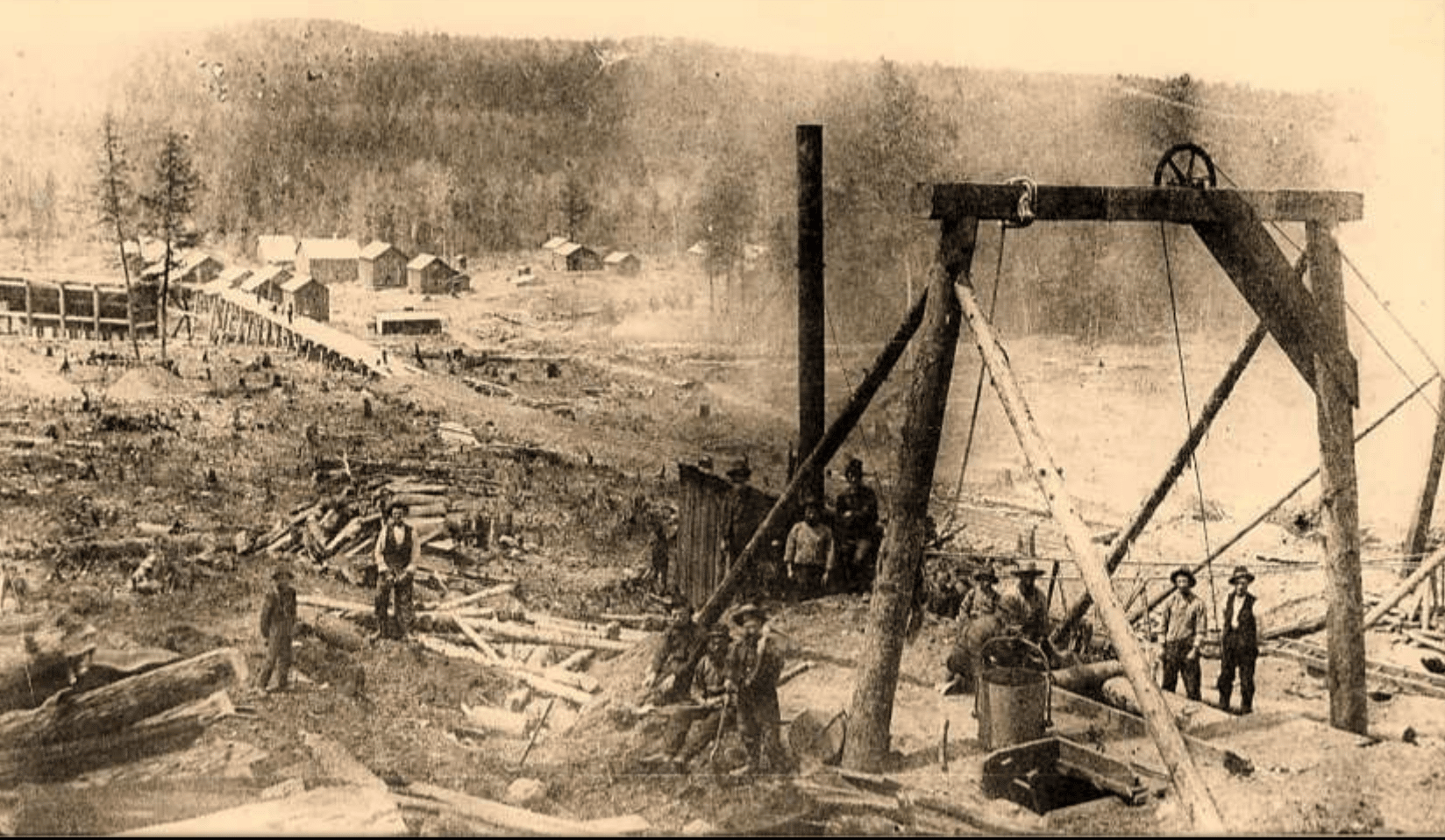

Iron Mountain, practically on the Wisconsin border, started as a mining town in 1878.

A year later, the same year the Chapin Mine broke ground, a merchant from Menominee on the shores of Green Bay 70 miles south arrived in Iron Mountain, pitched a tent, and started business. He was Charles E. Parent, my great grandfather, my grandmother’s father.

His name was new to me. I was just beginning to learn what I might have learned from aunts and uncles and cousins if I’d grown up near them. But my parents lived in North Carolina when I was born and later moved to Florida, about as far from Michigan as you can get. I was a small boy when Mom took me to her sister’s family cottage at Black Lake. I remember taking shelter during a tornado warning and coming out from swimming with a leech attached to me, but if there were family stories told I didn’t pay attention. So I had no idea about the Parent family and how entwined they and my grandfather’s family were with the history and development of Iron Mountain.

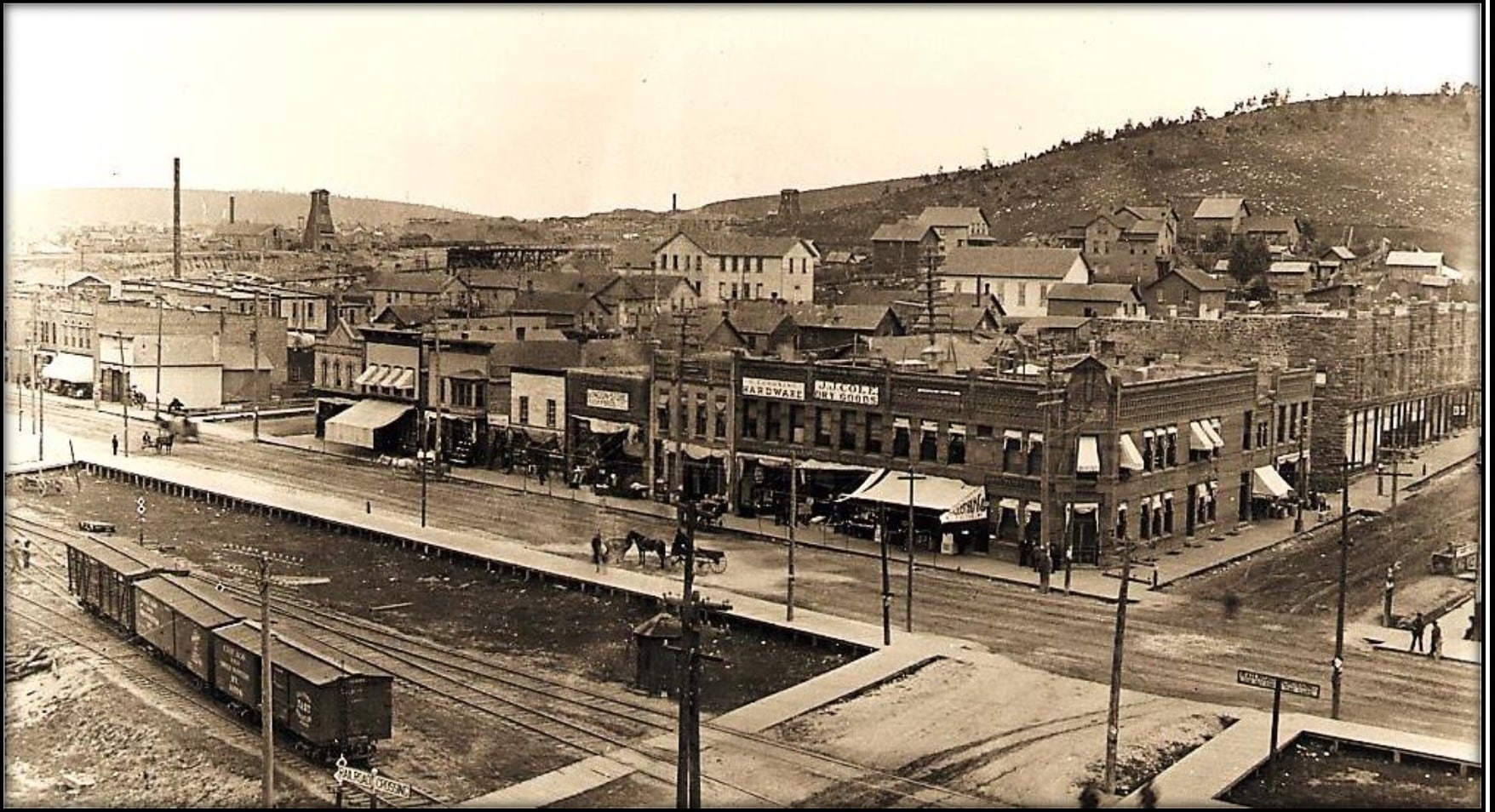

The Chapin mine prospered, not least on the strength of a powerful steam-driven pump engine that cleared water from the mine shafts so miners could remove the ore. The influx of miners and the success of the mines helped Charles Parent move from his tent to a main street. Iron Mountain soon had hotels, competing rail lines, a hospital, and an opera house.

The building was still under construction when patrons sat on seats made from planks and beer kegs to watch “Monte Cristo,” a stage version of the Alexandre Dumas novel. Rundle’s Opera House hosted a grand ball to mark the formation of Dickinson County in 1891. A year later, when the second floor was finally finished, a local historian wrote that “the good theatrical companies never forgot to stop in Iron Mountain.” And in April 1897, the opera house exhibited a newfangled machine, a cinematescope that showed “animated pictures that actually seemed to move!”

By then my grandfather’s side of the family had discovered Iron Mountain. Mandel Levy, his older son Henry, and a nephew he had raised as a son after his parents died in Ontario, Canada, arrived in town in 1887 from Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, where they had a department store. They were like other Jewish merchants all across America who perhaps started as peddlers and then set up shop in places where they saw there was business to be done.

The nephew was my grandfather, Isaac Solomon Unger, called Ike. His parents had come to Canada from Alsace, in what’s now eastern France around Strasbourg. Ike, with Mandel and Henry Levy, opened a branch of their Wisconsin store on South Stephenson Avenue, where Charles Parent had moved his clothing store. M. Levy and Company grew quickly.

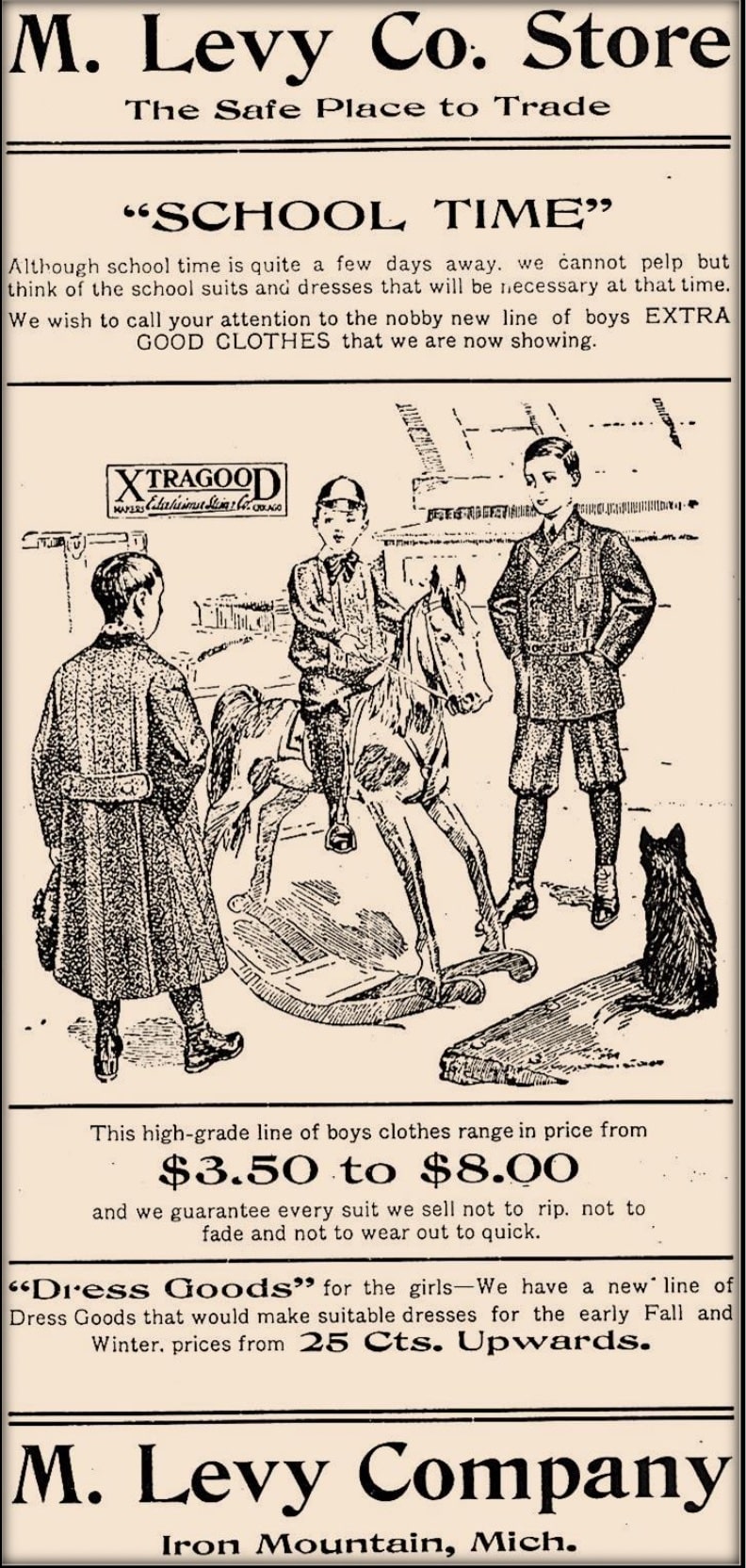

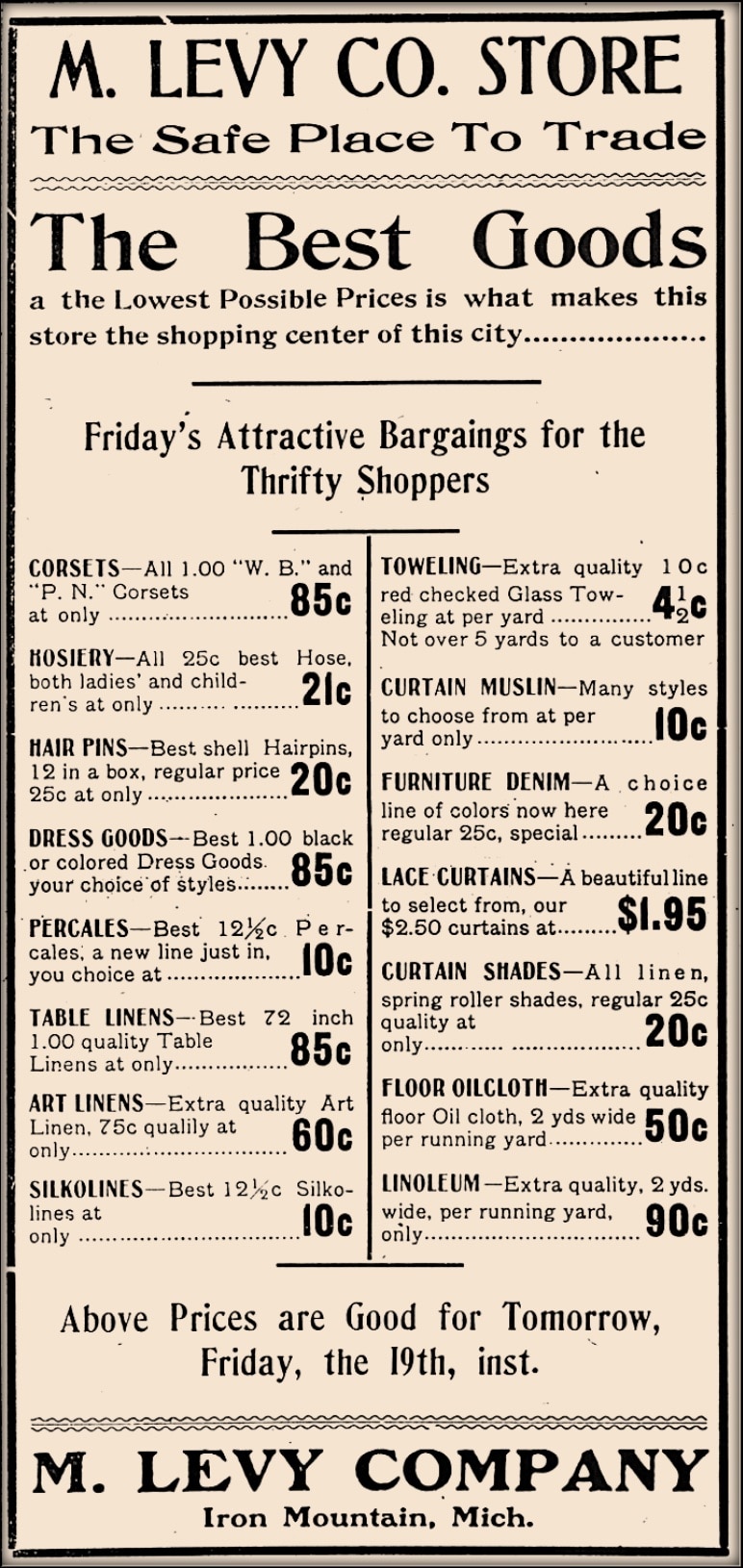

While the Parent store stuck to clothing, the M. Levy Company sold “Dry Goods, Clothing, Gents’ Furnishings, Groceries, Provisions, Flour, Feed, Boots, Shoes and General Merchandise.” It was so successful the partners sold the Wisconsin store to concentrate on Iron Mountain. Later a younger Levy son, Albert, joined the firm as did Ike’s bother Monroe. These newspaper ads, from the Dickinson County Library collection, stressed variety and price (and could have used some proofreading).

They eventually changed the name to Levy & Unger and Ike was doing well enough to propose to a woman from a prominent family.

Mary Parent, Charles Parent’s daughter, was 26 and Ike was 32. I wondered, going through this material, what it was like for a couple to get together at that point in their lives. It’s not unusual now, but then? They had retail in common and fashion. She ran a millinery shop on the second floor of her father’s store and Ike was a natty dresser. But while Ike was Jewish, Mary, called Mamie, was Episcopalian. That didn’t seem to matter. They married at her parents’ home in September, 1900, and honeymooned on the Great Lakes. Back home in Iron Mountain, they started a family. This where Judaism begins to get lost.

If Ike, his brother and uncle’s family practiced Judaism, they didn’t share it beyond the food they ate at the home of Mandel and Rebecca Levy.

[caption id="attachment_47847" align="aligncenter" width="794"] Young Ike Unger

Young Ike Unger

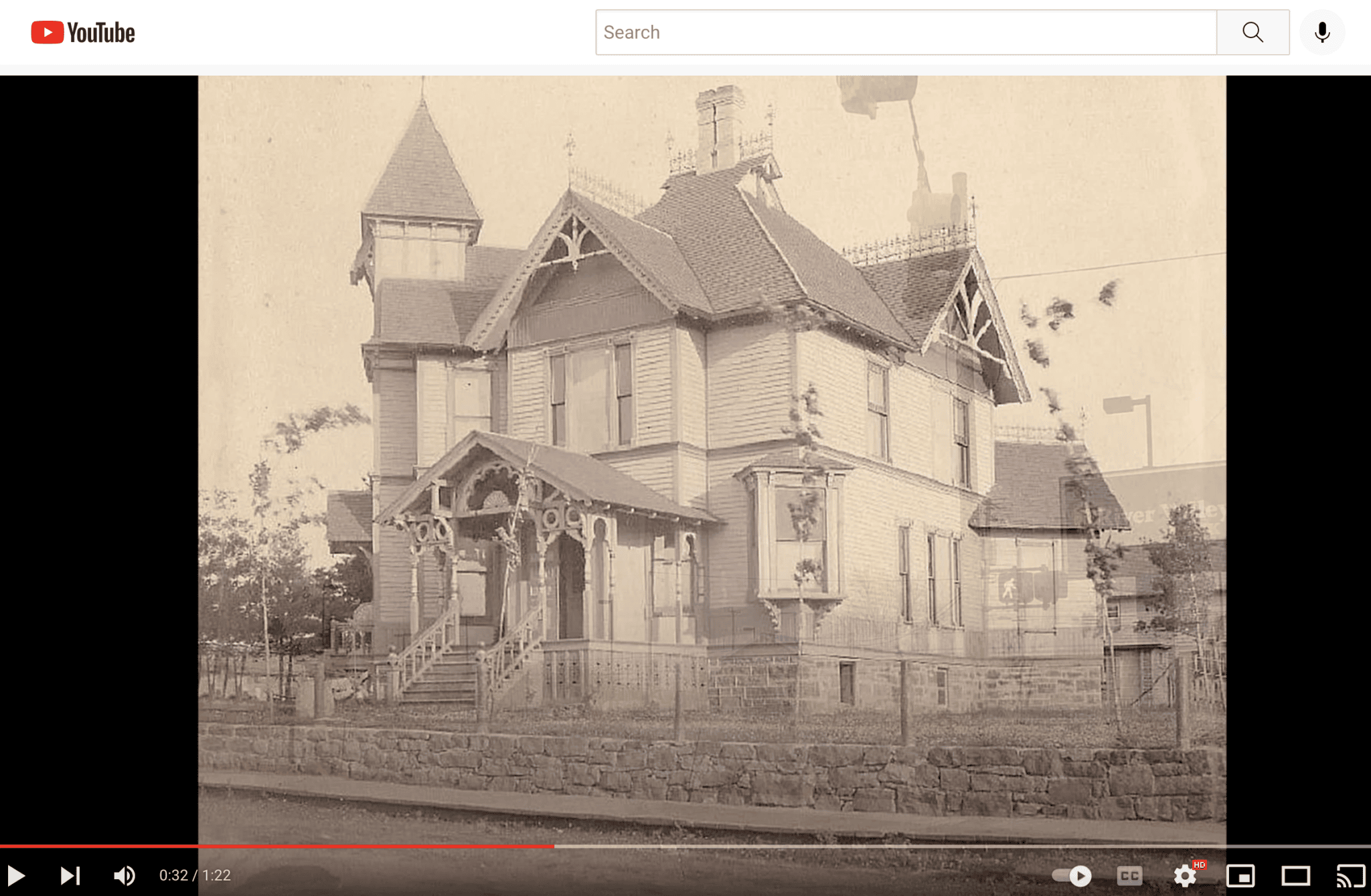

Clare, my mom, born in 1909, was the third of three girls and a brother followed her. Monroe, Ike’s brother, lived with the family in a big two-story house on a corner lot, and there was room for a live-in housekeeper as well. Mamie and the children went to church on Sundays, Ike and his brother didn’t, but Ike attended Christmas and Easter services where the children sang in the church choir. And as my Mom wrote in her personal history, “he never missed a church supper.”

He was a retail innovator and created dramatic store displays. He created drama for his children, too. They woke up on Christmas mornings to trees that hadn’t been there the night before. There was extra drama the Christmas that Mom and her siblings dashed downstairs to find that Santa had apparently forgotten them. Then their father “discovered” the fireplace flue was closed. He went on a search and found that Santa, unable to get down the chimney, had left the the tree and presents in the garage. Less dramatically, Ike also received patents for gadgets including a high chair seat for babies.

In the personal history Mom wrote for me, she said he loved the business world. “He followed every new trend. He thought the millennium had come, I guess, when Henry Ford came to our town, built a factory [in 1920] and paid his workers five dollars a day. This was the same Henry Ford who used to attend our high school football games,” she wrote.

And it was the same Henry Ford who purchased a weekly newspaper in Michigan called the The Dearborn Independent that he used as a vehicle to attack Jews and what he called, “The International Jew.” In 1931 Adolph Hitler had a portrait of Ford over his desk and when a Detroit News reporter asked about it he reportedly said, “I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration.”

It’s hard to know now about anti-semitism In Iron Mountain then. Maybe someone will read this story and share it with a family member. But for now, I can only imagine why my grandfather and his family kept their religion and heritage close. Their safety and prosperity were at stake. My mom always saw the best in people and she wrote that growing up Iron Mountain was “a regular melting pot with Swedes, Finns, French, Italian, Welsh, Poles, Arabs, Jewish people, and many more. We lived together in peace and harmony.” That wasn’t entirely true.

Although her father wore a yarmulke, Mom didn’t know that word. She called it a beanie or a skullcap, and thought he wore it to keep his bald head warm. She didn’t know she was Jewish and only years later recalled a childhood incident that she did not understand. She was bewildered when children from another family screamed, “Christ Killers,” at her and her siblings after they had an argument at an elementary school picnic.

In the meantime, her parents had become pillars of the local community. Her mother’s family claimed their history dated to the Mayflower. She was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and worked with the Red Cross. They golfed at the local country club and enjoyed dressing up and going out to dinner. Ike was a member of the Masonic Blue Lodge and in 1899, with other businessman, formed an association to crack down on chronic debtors. He even flirted with running for mayor of Iron Mountain.

Our visit to the town made me look closer at what my mother had written about her Jewish history. She had never told me that I was part Jewish until I met Barbara in 1976 and then it came pouring out. She wrote that she woke up late “to the fact that we did indeed have a part-Jewish heritage.” Apparently someone from Iron Mountain told people in a town where she was working that her family was Jewish. When she asked her Christian aunt and uncle about it they said, “What’s wrong with that?”

Ike Unger died of a cerebral hemorrhage in June, 1926. He was sixty, my mother was sixteen. That was the end of Iron Mountain for Mamie and her children. Not long after he died, she moved the family to Birmingham, a Detroit suburb. That’s where my mother later met my father.

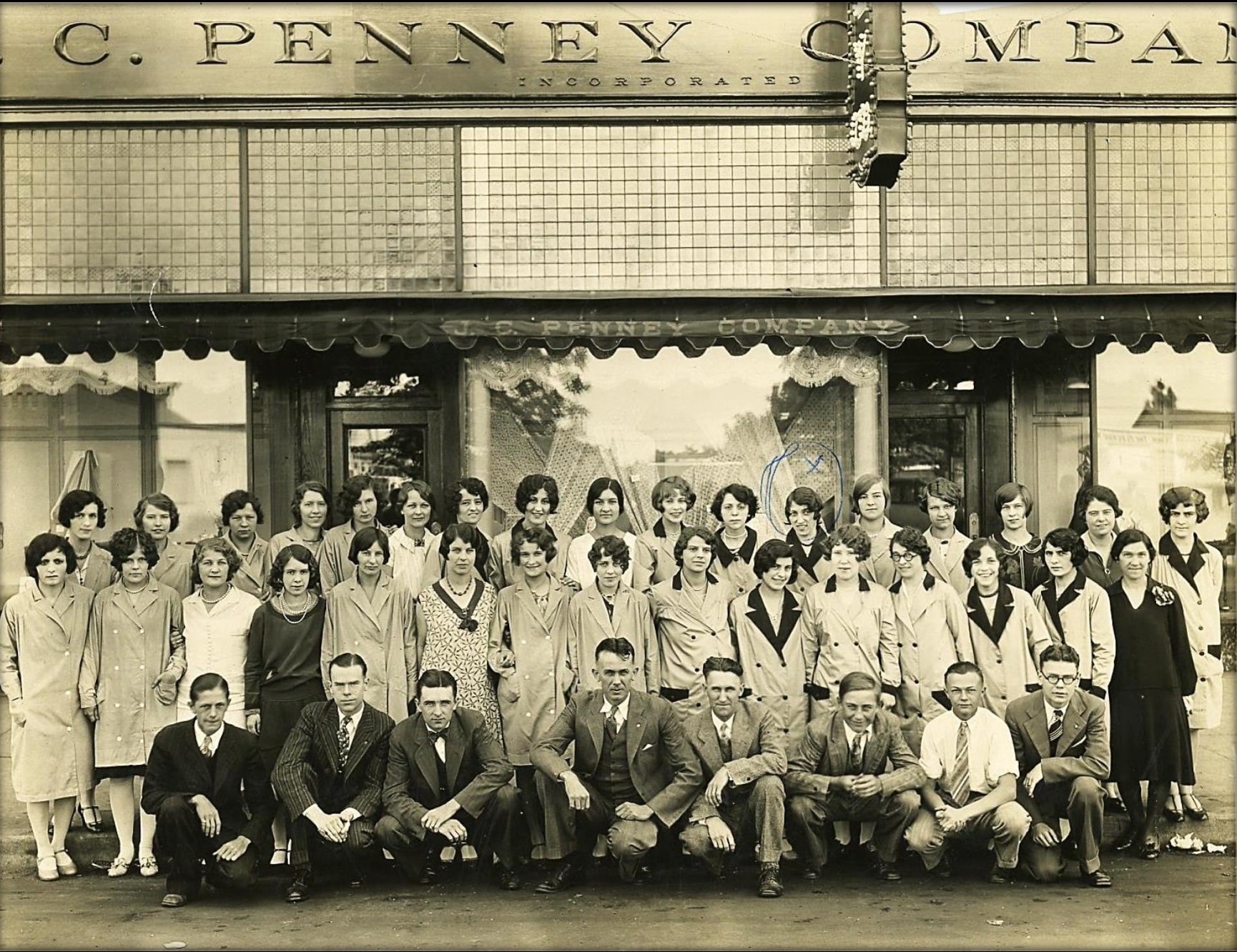

Prosperity also began to wane in Iron Mountain. The town had 11,652 people in the 1930 census. The Chapin mine that spurred town growth closed in 1932. Other mine closings followed and the population slowly dropped. The 2020 census counted 7,174 residents. The family store became a J.C. Penny in the Levy-Unger building from the 1930s into the 1970s, when it closed. The building burned to the ground in 1982.

And now in 2022, we walked on C Street where my mother grew up. Their house was up a hill in a tidy area of two-story houses a few blocks from downtown. The lilac bushes my mom remembered were gone but the house except for the siding looked as if it hadn’t changed much in almost a hundred years.It still seems like a nice community.

We visited the Iron Mountain Cemetery and paid respects to my vanished relatives.

[caption id="attachment_47943" align="aligncenter" width="2048"] My grandfather’s grave in Iron Mountain’s cemetery.

My grandfather’s grave in Iron Mountain’s cemetery.

We couldn’t touch them, nor could we revive lost conversations and moments that might have revealed more about their inner lives.

My mother struggled at points to find out more and to let me know that I had a Jewish grandfather and family. Well into adulthood, she covered religion as a newspaper reporter and decided to include the previously uncovered local synagogues. This opened her eyes to the Jewish religious calendar of Seders, Yom Kippur, Rosh Hosanna, and Chanukah. She wrote with some chagrin about her interview with a Jewish leader: “I called to ask him about the Chanukah celebration. I pronounced it Cha-Nuka instead of Hanukkah.” I was in high school at this time and one of my best friends was Jewish. She persuaded his family to invite me to their Seder, but didn’t explain why. She was trying. Finally, when I brought Barbara to meet her and my dad, the dam broke and the stories poured forth.

Now that I’ve been to Iron Mountain and have seen how remote the area is and how important it might be to belong, I understand a little. And knowing more about my family’s history, I know more about who I am. That’s why we went to Iron Mountain.

We also were on a travel adventure and were headed west. Come with us here.

And in case you missed it, take a look at our trip to Niagara Falls and Bay City, Michigan, here.

So glad you put all the pieces together, Nick. This is lovely.

Hi, Carolyn. Thanks so much, and thanks for reading. It’s never too late to learn family history. Please share if you feel like it. All best.