by Nick Taylor

It’s not over ’til it’s over . . .

In May, I learned that I still had cancer. I thought it had gone along with my prostate, but my surgeon, Samir Taneja, told me to keep getting PSA tests to be sure.

PSA — prostate specific antigen — found in the blood is a kind of protein that indicates when the body is fighting cancer. The first two tests found no detectable PSA, but the third, last December, found a trace, 0.06. That’s a small number compared to the 4.0-plus that prompted the original surgery, but it was there. April’s blood test came back higher, 0.22, and another less than two weeks later showed 0.33. The readings were low but rising quickly. I knew that that meant trouble. Taneja’s office ordered a PET scan.

The scan confirmed my suspicions. A small band of cells had escaped from my prostate before it was removed and found their way into a lymph node, where they were again at work.

My primary care doctor, Peter Zeale said, “You’re not alone. Two of my other patients had the same experience.”

Yes. But this was me. I won’t say I was scared, but I was eager to find out what I could do.

Taneja’s assistant, Samia Choudhury, beamed in for a teleconference. Barbara and I listened as she listed the options including radiation and a second surgery. I immediately said, “I want the surgery.”

A week later it was Dr. Taneja on the screen. He explained that he wanted to talk about surgery because, he said, “There are no studies that show that the surgery prolongs life.” Then he laid out the options, dictated by what we knew about the cancer’s timeline.

“We’re learning what is the right approach to this disease stage,” he said. “If we choose not to do the surgery at this point, the treatment for metastatic disease is to put you on long-term hormone therapy. Or the intermediary option, which is to combine hormone therapy with radiation, monitor and see if radiation durably controls the disease by stopping hormone therapy. If not, then long-term hormone therapy is what we would utilize in the future.”

Hormone therapy would mean taking estrogen to negate testosterone, as devilish a component of the male makeup as the prostate itself. Testosterone gives a man his sex drive. Estrogen would give me hot flashes, night sweats, and a higher voice, and weaken my muscles.

The argument for surgery was fairly strong, however. If my PSA had been high soon after the initial surgery, that meant cancer cells had already started attacking the area outside the prostate. It wasn’t. “The one thing that appeals to me about surgery in your case,” said Taneja, “is that the first evidence of relapse was about a year after surgery. So the more delayed the interval to the time that we detect relapse, the better the chances that a surgical intervention could be curative.”

But the lymph node would be hard to locate, he continued. “They’re tiny,” he said. “This one was six by eight millimeters [around a quarter of an inch] and we don’t have a real way of detecting them. So I will go in and clean out the whole area that’s showing up in the imaging. But the one is in a clear location and I think it’s less likely that we’ll miss it. Of course, the final pathology will tell us whether we’ve gotten it or not.”

“What would you do?” asked Barbara, who was also on the Zoom call. He thought about it and said, “I think I’d do the surgery.”

I agreed, and I wanted to do it as soon as possible. If aggressive cancer cells had migrated from the prostate to one lymph node, they’d soon move on from there.

The operation was scheduled for Wednesday, June 14. Routine pre-surgical testing on June 9 included a blood draw that put my PSA at 0.96, almost three times higher than the later April test. It couldn’t happen soon enough.

Barbara and I got to NYU Langone’s Kimmel Pavilion around 6:30 in the morning along with the arriving staff. We elevatored to an upper floor where the operating rooms are and checked in. I was shown to a prep room where I changed into a gown and stuffed my clothes and shoes into a purple hospital tote bag.

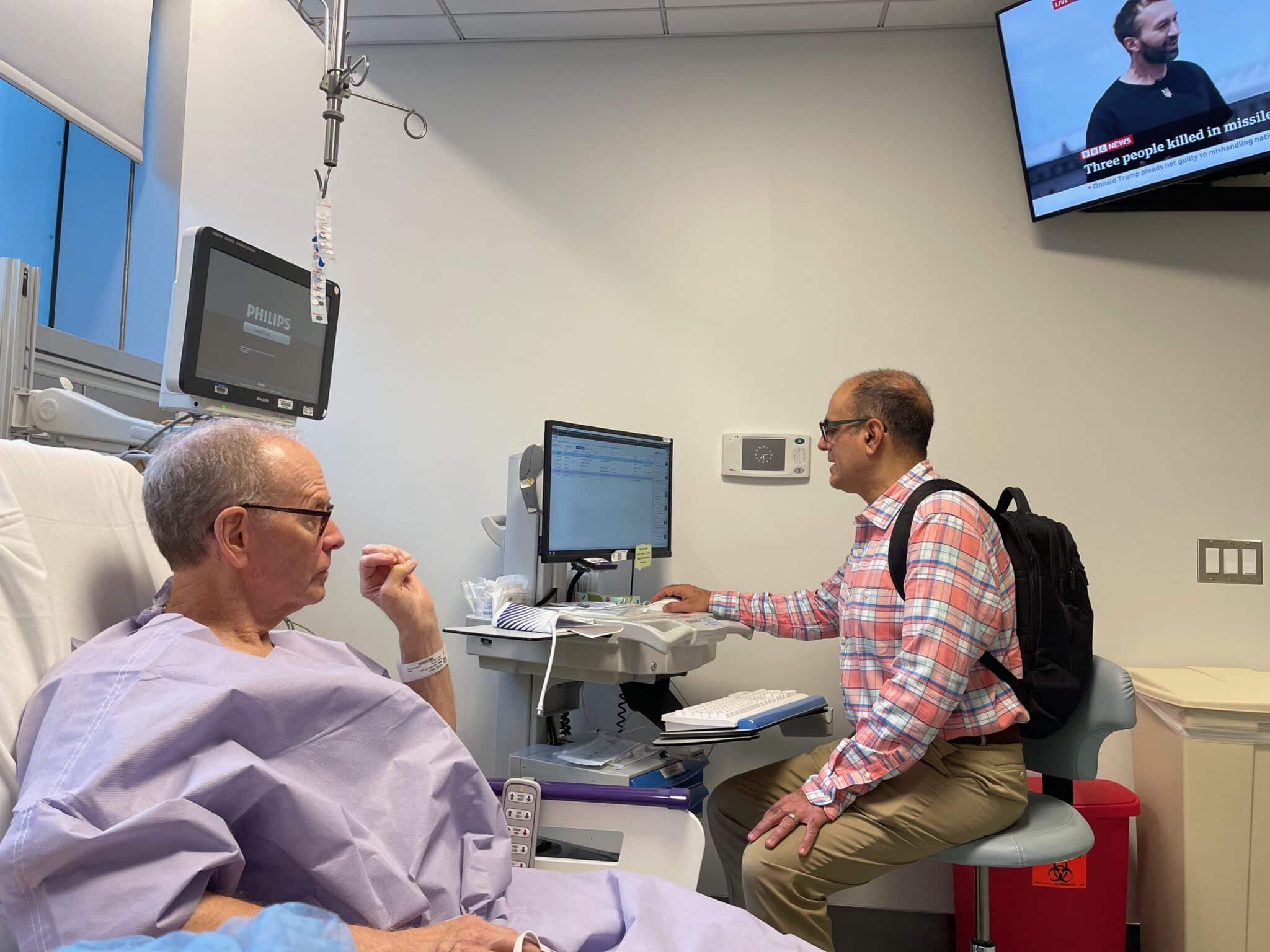

Barbara came in from the waiting room to keep me company. Dr. Taneja, with his backpack on fresh from his morning commute from New Jersey, stopped in to see if I had any questions.

Later I heard him asking a colleague if he thought the laparoscopic camera could find the lymph node he’d be looking for. I didn’t think that this would be a treasure hunt, and yet I pushed the negative thoughts away. I chose belief and maybe magical thinking instead. There was no choice really.

The anesthesiologist came in and stuck an IV in my arm. Then Barbara said goodbye and a nurse walked me into an operating room crowded with people and mysterious machines.

Once the IV was hooked up I was gone. This was a robotic surgery like the prostatectomy. Five new incisions across my stomach at the level of my naval mirrored those I’d gotten the first time, where the camera and instrument probes went in. I felt them as soon as I woke up. One in particular on the right side hurt like hell.

Tenaja had already called Barbara right after the surgery. It was about two hours after I’d entered the operating room, and she was surprised that it had gone so quickly. “It went very well,” he told her. “It was very small, just above the rectum. It looks like we got everything. But we’ll see what the pathology report says.”

Barbara came back to the hospital to get me and I was ready to go home. But the pain had raised my blood pressure and it had to go down before the hospital released me.

Some oxycodone and Tylenol did their work and by mid-afternoon I was free. Until I tried to tie my sneakers. My nurse had to tie them because it hurt too much to bend and reach the laces. Another nurse called for a wheelchair, but insisted that I didn’t need it. So we walked together to the elevator and found Barbara waiting in the pharmacy on the main floor. From there we walked outside and Barbara and I climbed into a car that took us home.

The pain was bad for a couple of nights. I took one oxycodone but Tylenol did the trick after that as long as I slept on my back. I eased back to a normal diet, and did a phone interview for a book proposal I’m working on. By Tuesday of the next week Barbara and I subwayed to midtown to eat lunch and again that night for dinner. I was functioning, but had the operation been successful?

MyChart posted the pathology report one week out, on Wednesday night June 21st. One group of seven presacral lymph nodes had tested negative for cancer. In one mesorectal lymph node, testing found “metastatic adenocarcinoma involving one of one lymph node morphologically consistent with prostate carcinoma.”

This sounded like Taneja’s post-operative report to Barbara. A call from him first thing Thursday morning confirmed it. “It’s the best possible outcome,” he said. He’d found the lymph node that showed up on the PET scan and removed it. Neighboring lymph nodes were cancer free.

A little discomfort is a small price to pay for that result. Cancer’s sneaky, though. On July 10, just short of four weeks since the surgery, I visited Quest Labs to have blood drawn for a PSA test. It came back at a barely detectable .03. So I’ll keep getting them.

In the meantime, Barbara and I have some traveling to do to places in the world we haven’t seen yet. Scandinavia is on the close horizon, including Kirkenes in northern Norway five miles from the Russian border. Maybe we’ll see the northern lights and be reminded, yet again, that health is a gift, life is precious, and time is all too short.

Thanks so much for posting this! It’s very kind of you to sacrifice your privacy to help others. As a retired internal medicine PA (28 years) and an endometrial cancer survivor, I know how much hearing about other folk’s experiences helps people feel like they’re not alone and gives them confidence that they’ll recover well. You’re really doing a good thing! I’m hoping both you and I are done with this nasty stuff. Good luck! It does sound like you’re done with this!

What an odyssey, Nick! Thanks for sharing; it was a captivating read, and I am very happy you are now on the mend and cancer free. Best, Sunshine