by Nick Taylor

We hadn’t traveled since the beginning of the COVID pandemic nearly two years ago. The months of lockdown and isolation took a toll, some physical, some mental. It was greater than I realized. I lost the ability to do things I took for granted; even the simple act of walking was harder, and my confidence eroded. Barbara and I never shied from challenges on our wide travels, but I wasn’t sure about the “twilight tour” at El Yunque Puerto’s Rico’s rain forest. Yet I agreed to go.

We failed to book in advance and discovered that was a mistake. On a Monday, we looked for a Tuesday trip. Spontaneity during COVID doesn’t always work. The U.S. Forest Service oversees El Yunque and limits the number of people who can be on the mountain every day. The day trips were all booked, but a twilight tour of El Yunque run by a private company seemed attractive.

We were staying on Puerto Rico’s southeast coast at Palmas del Mar in Humacao, an hour from El Yunque.

The roads in Puerto Rico are good but not as brightly lighted as they are in New York. We realized that we didn’t want to drive back down the mountain on a dark highway after the hike. So we looked for places to stay nearby. Barbara found The Rain Forest Inn, which looked lovely. They only have a few rooms and the owner Bill Humphries said they were booked three months in advance. He suggested that we try the Wyndham Grand Rio Mar Hotel just down from the mountain on the island’s northeast coast. “They have six hundred rooms. They must have something,” he said. He was right.

The next day we checked into the hotel, hung around for a bit and then we drove toward the Angelito Trail Head a few kilometers inside El Yunque. The road was twisty and narrow and we felt the magic of the rain forest as we followed the GPS directions to the meeting spot up the mountain.

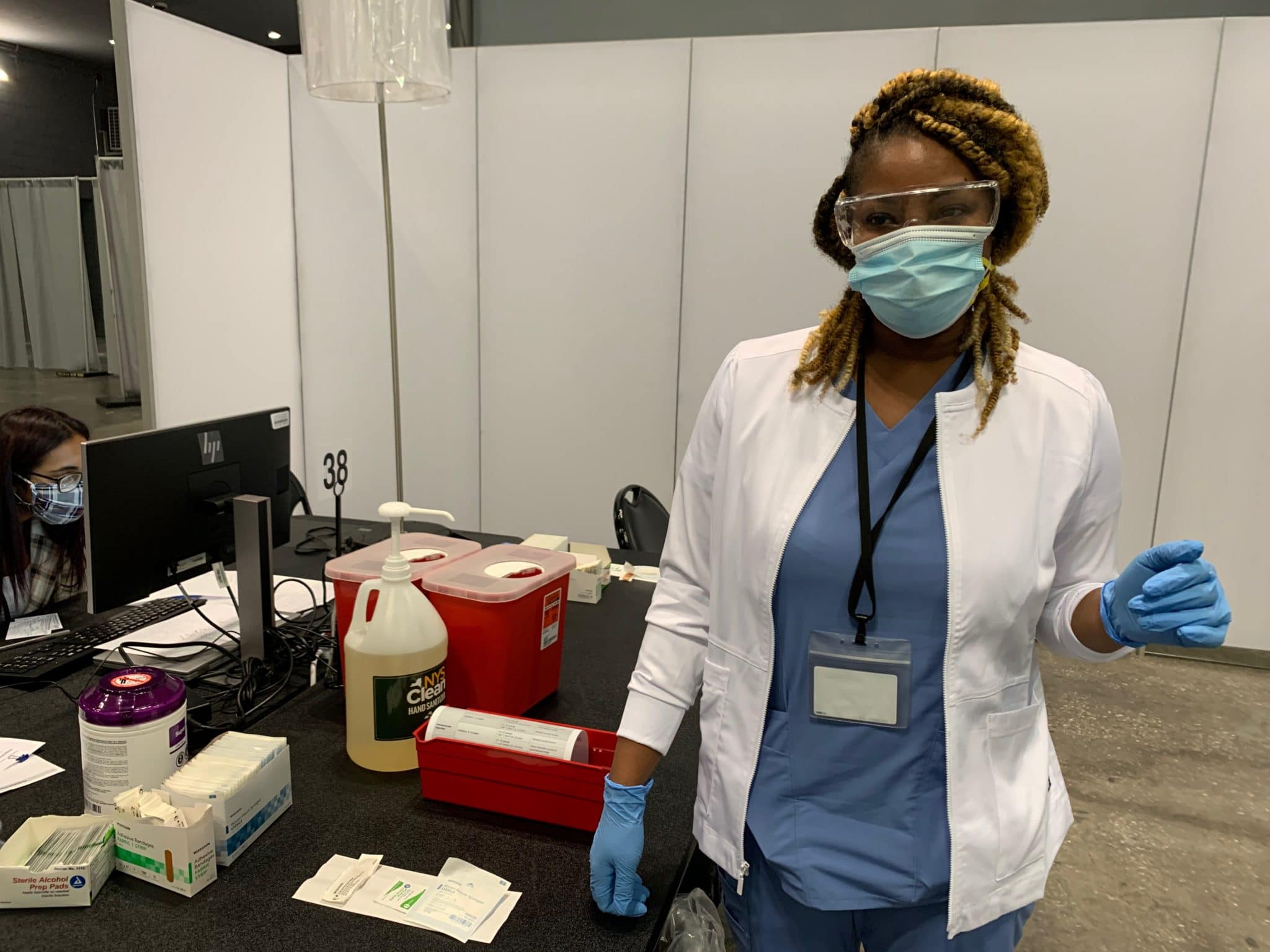

We had signed up and paid online and filled out disclaimer forms about our ability to do a little walking. The folks at El Yunque Tours told us to arrive a few minutes before the tour’s 4:30 start. Other cars were parked along the road when we got there, and Angel Robinson and Jorge Candelaria, our guides, waited by a van filled with gear.

Soon our group of about twenty, couples and families, gathered around a small table set with a tray of mango and passionfruit slices. Angel said, “Watch out for the passion fruit. It can lower your blood pressure,” and he talked about how he discovered that.

Turns out passion fruit contains ascorbic acid, and a National Institutes of Health study indicates it may have benefits for the heart. But on the mountain we were just discovering that Angel was a trove of information. “I’m one of those people who likes to know everything, ” he said. “I’ll probably tell you more than you want to know.”

Angel and Jorge handed out backpacks and towels, snacks, and water to fill them with. We set off toward the trail, Angel talking all the way. “Anyone know what U.S. state is both the easternmost and the westernmost?” he asked. “It’s Alaska,” he declared triumphantly in the silence. “It’s on the 180 degree meridian, so it’s both the farthest east and farthest west.”

We knew this was going to be a funny trip and I began to forget about my fears or concern about walking.

First we stopped to take a group photo and Angel explained that there would be two of those. Once we he took the photo, we began the walk down a path into the forest. “You won’t see any monkeys here. That’s a myth,” he said. “You may see scorpions and that’s about the most dangerous thing that you will encounter.”

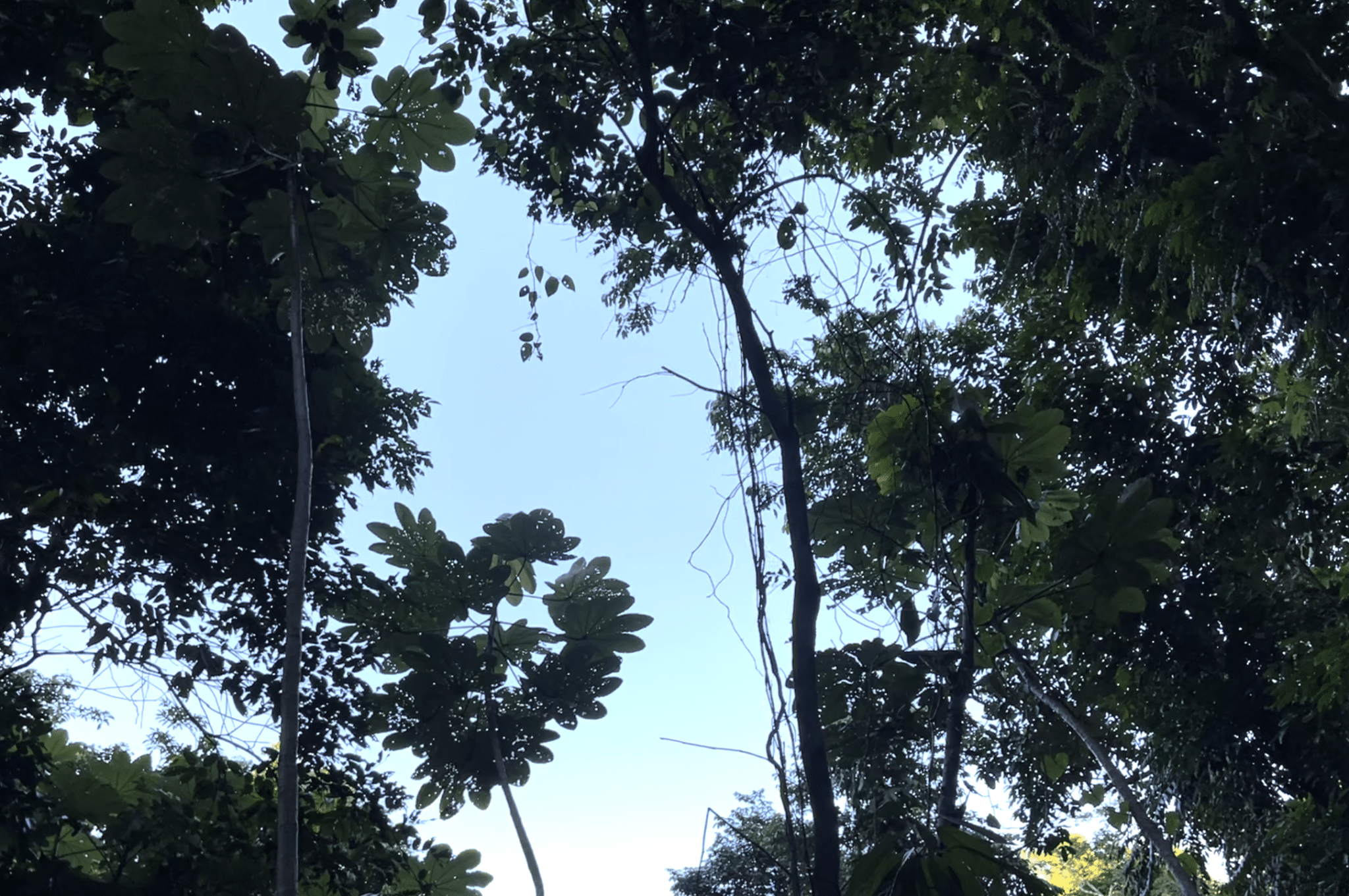

A short way in, Angel stopped to reveal that El Yunque wasn’t really a rain forest at the moment. Hurricane Maria in 2017 destroyed the forest canopy that blocked sunlight from the forest floor.

The low growth that spurted up made the forest more of a jungle, at least temporarily. When the tall trees grow back, many of the lower plants will die and the jungle will become a rain forest again. “One day wiped out 90 years of growth. It’ll grow back but not in our lifetime,” he said.

He also explained El Yunque’s name. It comes from the Taino, the natives who were here when the Spanish arrived. They looked to the cloud-shrouded peaks of the Loquillo Mountains at the heart of the 29,000-acre forest and called it Yuké, or white land. El Yunque is a modern corruption. He explained that Puerto Rican Spanish is a hybrid language that incorporates Taino terms not heard in Spanish elsewhere. “You Spanish speakers can’t understand us sometimes, right?” Angel laughed. He also pointed out that we use Taino words in English. When we talk of hurricane season, the term descends from hurakan, Taino for “god of the storm.”

He showed us the leaves from some trees that turn inside out and show white when the weather turns stormy.

He also talked about how much the Spanish learned from the Taino about the medicinal properties of plants and trees and found coffee and cacao. The skinny tree below is a cacao tree.

But the coffee plantations and timber cutters threatened the forest in the 19th century and King Alfonso XII of Spain proclaimed it a reserve in 1876. Spain ceded Puerto Rico to the United States in 1898 to end the Spanish-American War, and President Theodore Roosevelt declared it a forest reserve in 1903. That makes El Yunque the second oldest national forest in the federal forest system. Only Yellowstone is older.

We walked a little farther along the descending trail before Angel stopped us to explain the difference between native, or indigenous, plants and those that arrived naturally from somewhere else by wind or water. Endemic plants, as they are called, differ from invasive species because they got here on their own. To illustrate, Angel called attention to the black mask he wore over his nose and mouth: “I’m allergic to the dust that blows here all the way from Africa. Seeds could get here that way, too.”

He explained that coconut palms are endemic and planted themselves after slavers and other sailors dumped the coconuts that they had used as ballast to steady their ships. “The trees just planted themselves and now they ring the island,” he said.

He moved on and stopped beside the tangled base of a big tree.

Hurricane Maria, he said, had blown it down across the trail. Crews that came to clear it found the wood almost impossible to cut. “This is ausubo,” he explained, “the world’s second hardest wood.” He then spun a story of Sir Francis Drake’s 1595 defeat in the Battle of San Juan that you don’t find in the history books: Drake’s fleet failed to sink the vastly outnumbered ships of the Spanish defenders because they were built of ausubo and the English cannonballs just bounced off. Indigenous to Puerto Rico, it’s the island’s most important timber tree because the wood can last 500 years.

One of our group, a grizzled New Jerseyian named Mick, helped Angel explain another fact of the rain forest. “You can’t tell this tree’s age because it has no rings,” Angel said, pointing to the stump of the ausubo. “Does anybody know why it has no rings?”

“Because there are no seasons here,” Mick said astutely.

Angel looked a little surprised. “That’s right,” he said. “Puerto Rico has no seasons, so none of the trees have age rings.”

We stopped a few more times to gather around Angel as he told us more about the forest, of tree sap with medicinal properties and breadfruit trees and thin straight branches hollowed out as blowpipes to deliver medicine.

He showed us a huge stand of bamboo that had been planted by the Forest Service to stop erosion along the path. Bamboo is invasive and grows very quickly so it was a good solution for the changing forest.

We heard rushing water and the sound grew louder at each stop. Then the trail brought us past a waterfall to a river pool big enough to swim in.

El Yunque Tours had told us to plan on swimming at this Las Damas pool, and Barbara and I peeled down to our swimsuits and with the kids and few other adults waded into the cool water.

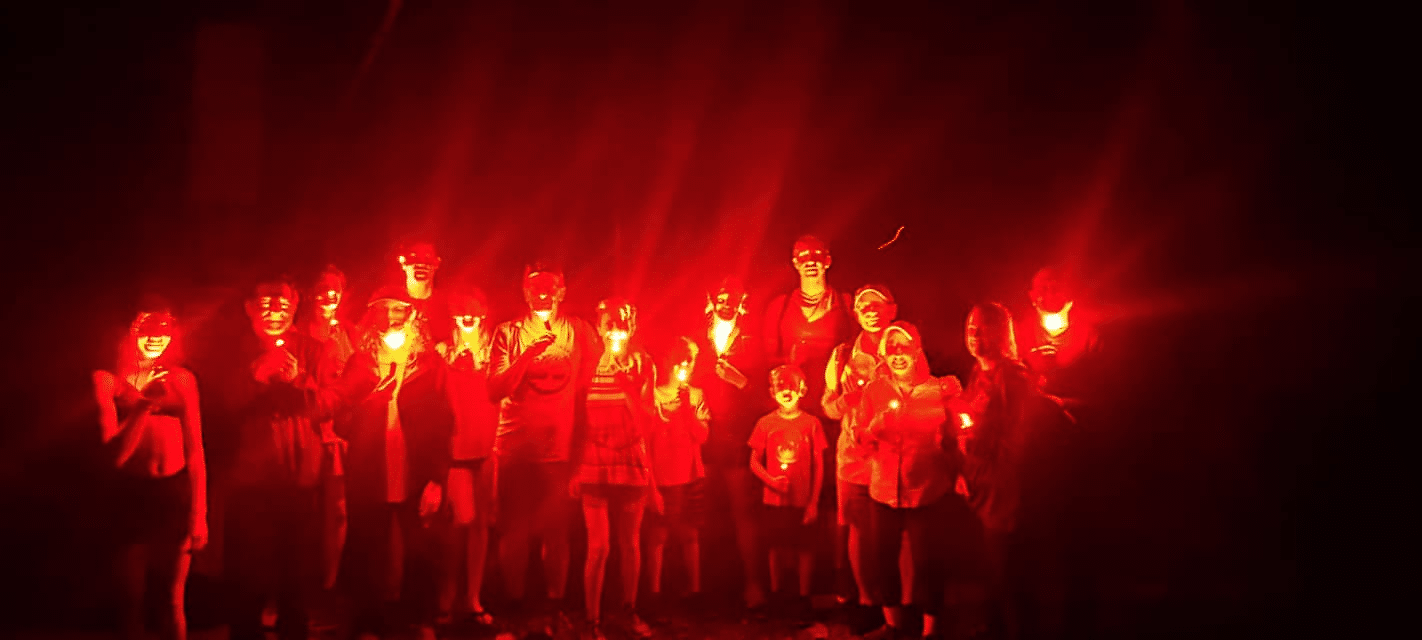

Some of the kids who wanted to make a big splash swung from a rope dangling from an overhanging tree. In a few minutes we toweled off and changed as twilight fell. Angel and Jorge handed out small red flashlights. These would light our climb back to the trail head without disturbing the night creatures we passed. But first we paused to take a photo.

We walked through a concert of night sounds. The dominant instrument played, “Co-qui, co-qui” over and over in countless overlapping repetitions. These were the mating calls of tree frogs named for the sound itself, Coquis.

Seventeen varieties of the species live in El Yunque, and all of them must have gathered to serenade our ascent along the trail. They were close, at our shoulders and elbows, and when our red flashlight beams found them it seemed impossible that such tiny creatures could make such large sounds.

The male coquis were smaller than a quarter. The females they were propositioning are larger, but they were high in the trees out of sight as they weighed which of their suitors had the most appealing call. Angel said, “The male sings and the female climbs up. She stops to make sure she likes his singing and then the male sings again and they do this some more until they finally get to the top. And then it’s a role reversal. She lays the eggs and leaves. He builds the nest and stays with the eggs until they hatch.”

Jorge stayed behind with us and helped us spot the tiny frogs waiting for their favorite love song. “I grew up in the mountains and I love nature. I like sharing it with people. But I need to work on my English,” he said. “We’re trying to learn Spanish, so we understand,” I said.

The red lights gave us a glimpse of the bioluminescence in the forest. “You see much more of it in the warmer months,” Angel said. But we did see glimmers of it in the low branches and on the forest floor.

In the middle of the walk back up, Angel squatted down and put his light into a little natural carve-out in a tree stump. “Here, look!” he said. “There’s a scorpion.” A few of us bent down to look and sure enough there was the black arachnid curled up ignoring us.

This wasn’t the one we saw. But this is what a scorpion looks like. Photo by the U.S. Forest Service.

Back at the trail head, we turned in our backpacks and towels and took stock. Angel and Jorge had been great guides, but I felt something greater than even the fine tour they had given us.

It was the exhilaration of remembering exhilaration, of knowing adventure still existed after the bleak pandemic months, of feeling whole again. I turned a corner that night, and I look forward to the path ahead.

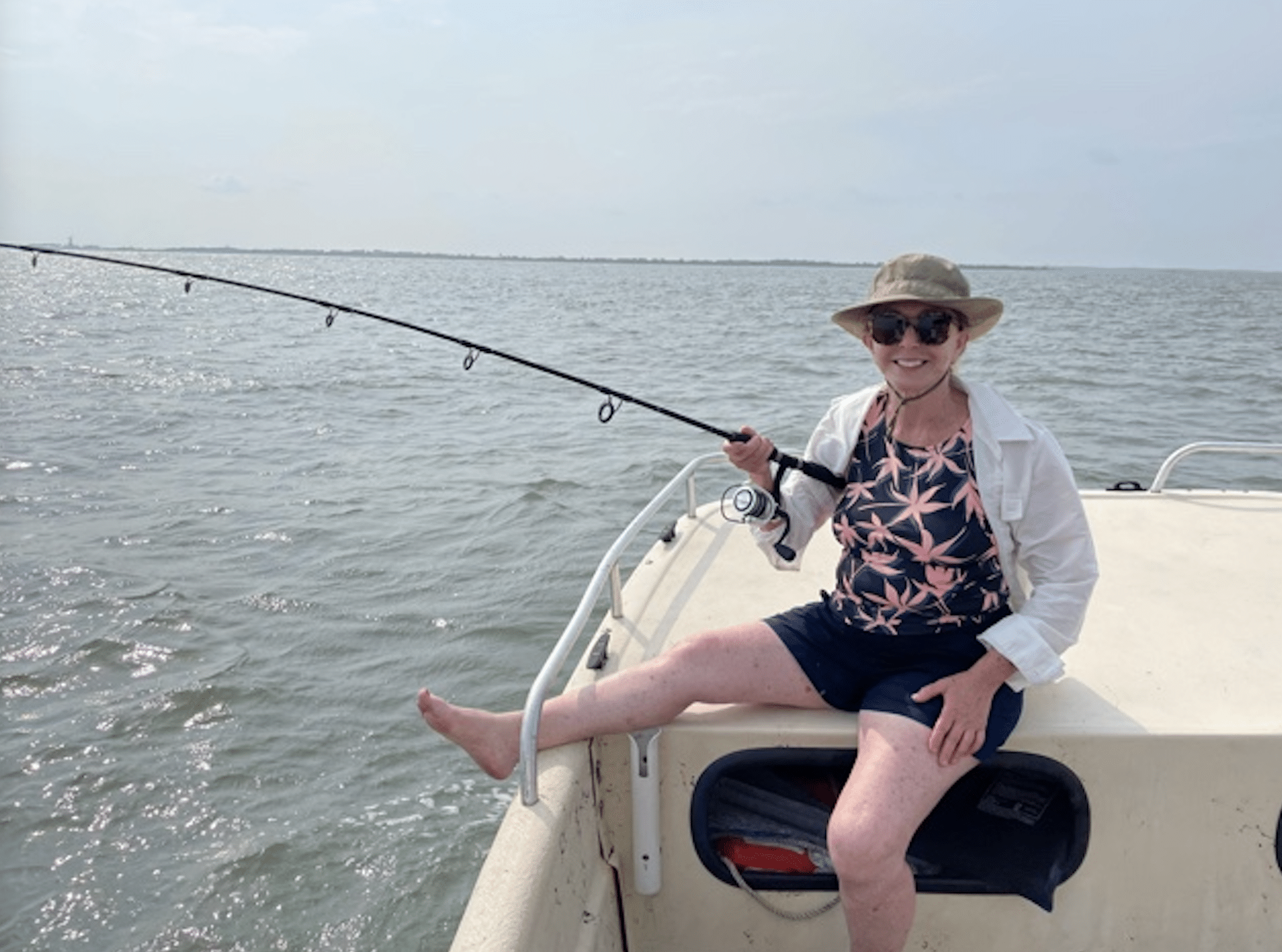

Fish Tales “everything trip” cost $276 for four hours. That meant we could spend the time fishing, clamming and crabbing, or just sightseeing. Clamming, though, demanded low tide. On my birthday, that meant a 1 p.m. start, and that would give us a leisurely morning. “Bring socks,” Jan told him. “Or if you forget we’ll give you some.” We would learn why when we got there.

Fish Tales “everything trip” cost $276 for four hours. That meant we could spend the time fishing, clamming and crabbing, or just sightseeing. Clamming, though, demanded low tide. On my birthday, that meant a 1 p.m. start, and that would give us a leisurely morning. “Bring socks,” Jan told him. “Or if you forget we’ll give you some.” We would learn why when we got there.

Ponies get herded to corrals and are auctioned off. Photo by Leonard J. De Francisci. Creative Commons License.

Ponies get herded to corrals and are auctioned off. Photo by Leonard J. De Francisci. Creative Commons License.

The adult snowy egret has black legs and yellow feet. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com

The adult snowy egret has black legs and yellow feet. Photo by ConsumerMojo.com