by Nick Taylor

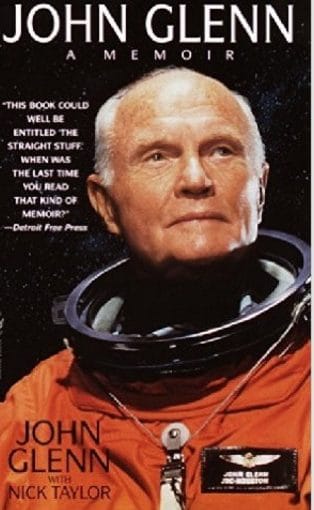

I knew John Glenn and worked with him closely as the co-writer of the best-selling John Glenn: A Memoir, published in 1999 after his return to space. With his death December 8 at ninety-five, the media calls started and I began recalling John’s intimate side, the things that made him our last great national hero.

John was special because he never acted like a hero. He never gave an air of being privileged or entitled. I never saw him treat a celebrity differently from someone unknown; he responded as if they all deserved his time.

The first time I met him was in his Senate office. He was in the last year of his fourth term and was calling it quits to train for a return to space as history’s oldest astronaut, thirty-seven years after he’d been the first American to orbit the earth. Amid this flurry of events, he was sitting at a large round table with a stack of photographs in front of him. He signed them one by one without an auto-pen in sight. His public deserved his personal signature as well.

The definition of what makes a hero is a lot cheaper than it used to be. I think a hero is someone who does what needs to be done no matter what it takes, who believes that that is what’s expected and it’s no big deal.

John grew up in the Depression of the 1930s. He thought his family would break up until his father, a plumber, found a job working for the Works Progress Administration, the New Deal program that provided work for millions of jobless Americans. His country had kept his family together, and in the small town of New Concord, Ohio, patriotism ran in the blood.

So it was natural that he became a Marine combat pilot during World War II and flew in combat again during the Korean War. He was curious enough and brave enough to want to know what he was made of, so after Korea he became a test pilot and set a transcontinental speed record. He and a ten-year-old Mississippi boy partnered to win the grand prize on “Name That Tune.” And then the Mercury program selected him as one of seven original astronauts. All because he was determined and brave and didn’t swell up about it.

The nation watched rapt during his orbital flight in February 1962. Many gathered in front of department store windows where TVs on display played the live broadcast. And we held our breath in shock and fear when, on re-entry, ground control lost touch with him. And when we heard his voice again and knew he was safe, the relief breathed out from coast to coast.

He became such a hero after that flight — the biggest ticker tape parade in New York’s history — that President John Kennedy kept him from another flight. He thought the nation couldn’t stand to lose John Glenn. Which was fine with John’s wife Annie but not with John.

Annie was another quest of John’s. They had always been together. She stuttered, and he didn’t care. But when the spotlight fell on him it fell on her as well. His life wasn’t whole without her beside him, and when they learned of a promising program that might help her conquer the affliction she signed up with his support. It worked, and Annie became as bright a public figure as her husband.

John’s Senate career and his brief presidential bid came from the same place as his military and NASA service; it was simply what you did for your country. He believed government played a role in people’s lives and he wanted it to be good and effective in that role.

But he never gave up wanting to go back into space, and in the late 1990s convinced NASA to put him aboard a Space Shuttle flight to, among other duties, be a human guinea pig to see what would happen to the elderly in space. He was seventy-seven when Discovery launched in October 1998. He orbited this time for nine days instead of the five hours and three orbits of his first flight.

That first time, he saw the sun rise and set three times. He told me that what he saw through his small window was an ecstatic beauty, enhanced for the first time by new colors against the curve of the earth. “I collect sunsets,” he said. “Photos, but mostly memories, from the time I was young. They’re God’s masterpieces.” He would remember his first sunset from space.

Even after his second flight, the renewed attention, the accolades that came with it, John never lost the common touch. Once Barbara and I dined with him and Annie when he was in New York to receive some award. They were staying at the Pierre Hotel, and John noticed that guests put their shoes in the hall outside their rooms to be shined overnight.

“I don’t understand that,” he said. “I can shine my own shoes. I always have.”

Beautiful, moving appreciation of a great man.

Thanks. We need more like him.